1. Falling into the delivery platform trap.

By Nuria Soto

This text will be published in two parts, this is the first part.

The arrival of delivery platforms in Spain around 2015 was a new and in fact attractive phenomenon for many of us who started working at that time.1 Glovo was officially launched in March 2015 in Barcelona, and the UK’s Deliveroo landed in Spain in November of the same year. The Belgian company Take Eat Easy arrived in Barcelona around the same time. It closed a year later, leaving several delivery drivers – many of whom would later become colleagues of mine at Deliveroo – without pay. This new working model was completely novel. The trade unions and the media also lacked knowledge and information about it. This meant we, the first workers to set off on our bikes with a rucksack and logo, were left with a whole road ahead of us and a labour conflict to recognise, understand, and face.

Passionate people wanted for a full or part-time hobby.

When I started working at Deliveroo in 2016, the company’s approach to attracting workers was quite different to what it is now. Back then Diana Morato, Deliveroo’s general manager in Spain, presented the job as if it were a sort of hobby, aimed at students and young people who were keen cyclists, and who were looking for a complementary, flexible activity to generate extra income. I fit that profile perfectly. I was a student at the time, I liked cycling and I was looking for something to complement my other two jobs, from which I didn’t make enough to pay for university and living costs. And it wasn’t just me. Even today, when I meet up with the many friends I made doing this work, practically all of us ride our bikes and go on rides together. We share that passion for cycling.

It was with this speech that I was sold the work in the first training session you had to attend before starting. You sat in a room with a projector and the company explained with a power point what this kind of flexible hobby you were going to be paid was all about. It was picking up and delivering orders, managed through a company-owned app that I had to download and log in with a username and password they would give me. If you didn’t want to work weekends, no problem, we were told. Within all the good news and information on how things worked, there was just one small final detail. I had to register as self-employed. In my ignorance, entering this new labour sector seemed like a mere formality to me, until I went to the offices to register as self-employed and the official asked me, “Are you sure?” In fact, it was not ” a simple formality”. It meant, among other things, a monthly expense that soon became a huge burden. As it was mandatory to register as self-employed, we had to pay a monthly fee that starts at 50 euros in Spain and increases every six months to a year, until it’s almost 300 euros.

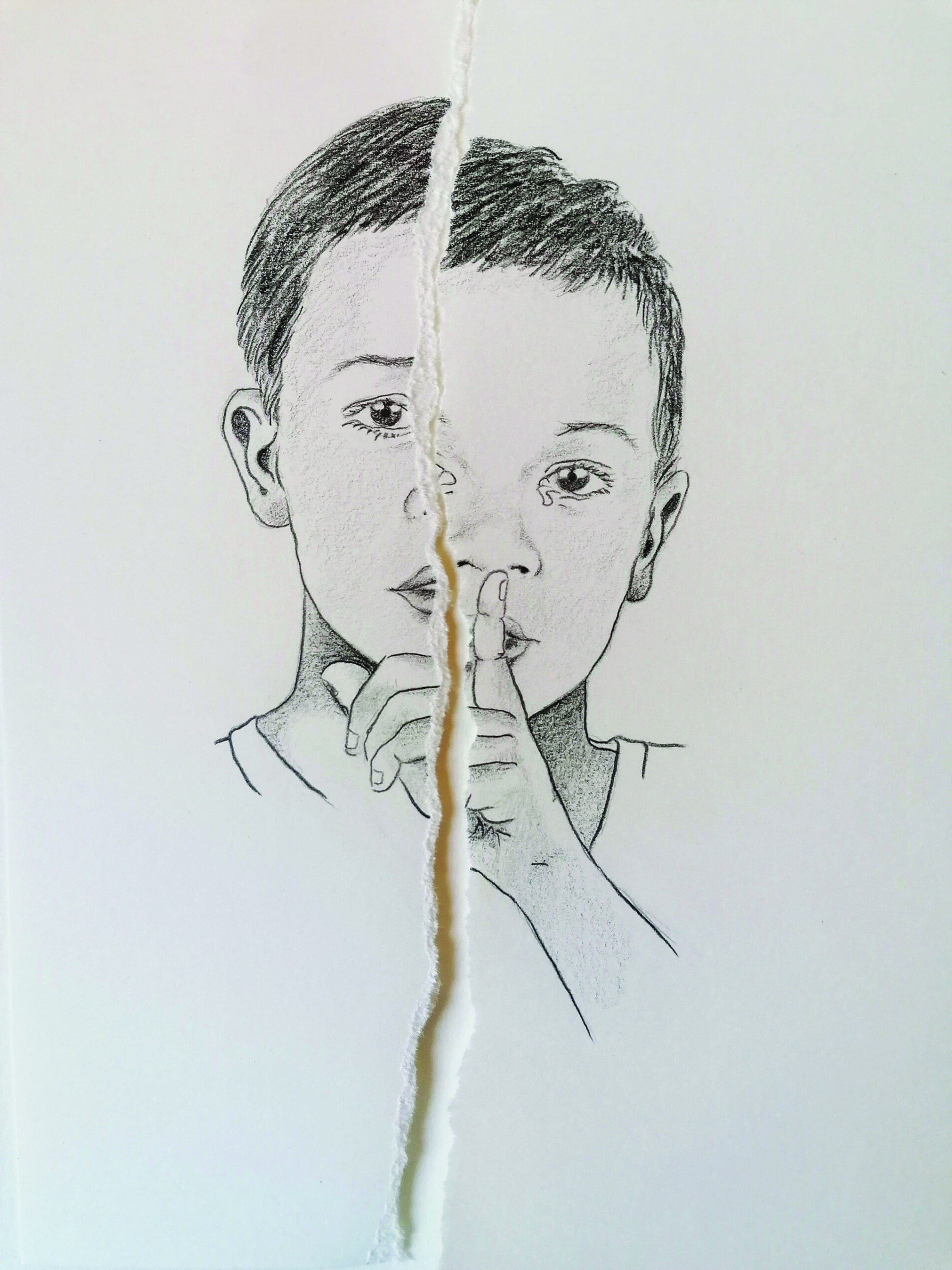

Understanding what registering as self-employed meant eventually led to the realisation that this approach concealed an entire strategy by which the company could bypass our working rights. The equation was simple: as delivery drivers, we had a myriad of obligations to the company, subtly camouflaged in the technological engineering of the platform economy. Because we were freelancers, we had released the company from any obligations to us. We were, in short, falsely self-employed. The app structured all our work down to the smallest detail (slots, shifts, hours, orders, zones), setting the conditions under which we had to deliver from the top down. As if those futuristic science fiction films and books about artificial intelligence were materialising in the present, the app seemed to be a virtual entity with a life of its own. Work took the form – in some kind of digital utopia – of a relationship between us and a screen. There was just one small detail that nobody seemed to want to acknowledge. The app had no life of its own, it had been developed by the same entity that owned it, which was none other than the company we worked for.

There were around 300 Deliveroo delivery drivers in Barcelona in 2017. However, these numbers multiplied exponentially year after year. As the business grew and it began to cement its presence in the market, the initial narrative of the “student who likes cycling and is looking for a hobby” morphed into a model that presented riders as entrepreneurs who were running their own company from the back of a bike. This discourse was based on values that the employers took great pains to communicate. They flew the banner of flexible, innovative, bossfree work.

In the beginning, if someone was simultaneously active on two or more delivery platforms and Deliveroo found out, they could “disconnect” you, which was what they called termination, and you could never log back into the app. Now, as a self-employed entrepreneur, you can work on multiple platforms at the same time, and work long hours from Monday to Sunday. Platforms like Glovo started allowing workers to log on to the app for up to twelve hours at a time. The eight-hour limit set by our labour legislation did not apply. It does not exist in the world of platforms. This change went hand in hand with the imposition of a new contract. We were no longer guaranteed a minimum hourly rate, but were paid per order delivered. Under the old contract, we were guaranteed 8 euros per hour, the equivalent of two orders, regardless of whether fluctuating demand meant we were able to deliver them or not. So, even if demand was low, we riders were guaranteed a minimum that allowed us to cover some expenses (expenses that the company saved thanks to their model of work and contracts), such as mobile data, bike maintenance costs, petrol, and even our social security. But now we were no longer going to be paid a minimum hourly rate. Our income was dependent on demand, our delivery capacity, and a set of unknown factors that determined the allocation of orders.

Now everyone had to keep their fingers crossed that they would get an order, personally taking on the risks of market fluctuation, the high and low levels of demand. But, above all, precisely because of these fluctuations in demand, they had to compete with the rest of the riders to get as many orders as possible. This had the effect of turning your colleagues into increasingly unknown competitors, as the platforms grew exorbitantly on this cost-free model in contracting expenses and payment for orders. With the new system, the boundaries between work and non-work blurred, and the time delivery drivers spent waiting for an order to come in was no longer considered work (even though it is work). The working day was thus extended well beyond eight hours, as working time was no longer regulated by a schedule, but by the number of orders you needed to deliver.

It was at this point that the zone centres or “centroids”, which were the places we returned to in each neighbourhood after finishing an order, also disappeared. This meant we lost the rest breaks when you could meet up with your colleagues, the wish to take a specific order so you

could finish the conversation with an buddy in the same area, the moments of sharing discontent or indignation, the impromptu football matches at quiet times, the orders rejected by the customer that we would keep and share with the others. (When this happened, it was customary to inform the Telegram group and meet up at the centroid to share the meal). In short, everything that made the person next to us someone we knew and loved disappeared. This all happened through the work and the centroid as it would probably not have happened in any other context due to different ages and backgrounds. We were quite a diverse team. When someone went down, i.e. was “disconnected”, it hurt all of us. When a colleague’s bike was stolen, we would meet up in our own time to go and look around the city, especially in the areas we knew we might find it. We got a few of them back that way. Basically, we shared and supported each other.

With the centroids, the Telegram channels that connected us to other riders also disappeared, and the support chat was introduced within the same app. In short, everything that had allowed us to organise with a union and start to fight back was taken away. Those of us who refused to sign the new commercial contract that no longer guaranteed a minimum hourly wage, as our own contract was still in force, were the same ones disconnected by the company for leading the 2017 strikes and demonstrations. We saw how, for the remainder of our colleagues, a new stage began. This stage consolidated the path that had begun a few years earlier: labour deregulation leading to the loss of rights.

A new scenario was thus emerging in which riders began to accumulate endless hours of work in a kind “self-imposed exploitation”. The new labour framework inevitably pushed you into it, if you wanted to make ends meet and cover your minimum expenses. This is a perfect set up for all those people who are not eligible for the minimum wage, who need to send money to their countries of origin, who are undocumented, who have to survive in a labour market in which all other doors are closed to them.

In fact, the profile of the workers on the large delivery platforms in Spain today is already mostly migrant, racialised, committed to sending money back to relatives in their country of origin, moonlighting, and part of the growing class of the working poor, who have problems making ends meet or do not make ends meet at all despite spending most of their waking hours at work. The structurally unequal conditions imposed on some may explain why the interest of the big platforms has been directed, to an increasing extent, towards migrant labour. What type of worker is more likely to be afraid to denounce the systematic violation of labour rights that this model of work implies? Who is more likely to accept the economic deal offered by the company in an attempt to avoid going to court? If the birth of the trade union platform Riders X Derechos (Riders for Rights) and a large number of legal complaints that made it to court were the result of a more privileged group of riders (mostly students in search of extra income), the change in worker profiles changed the game for trade unions as well. The demand to respect labour rights was often put before the obligation to cover basic economic needs with no alternative in the labour market. Who could have imagined that, in the end, the big platforms were not going to offer you a hobby with a small income, but a new economic and employment model that is here to stay?

Throughout its existence, those who have joined the trade union struggle in the Riders X Derechos collective – which I belong to – mostly have a Spanish background. We are all working class – defined by the condition of having to sell our labour power to survive – and we come from precarious working situations and contexts. However, we are different from our migrant colleagues in that we are regularised within the system. This means we have access to rights, support networks with greater economic resources – whether family or otherwise – that help us get by even when faced with sudden drops in income, and a level of whiteness that does not close the doors to other niches in the labour market. The decision to forego the almost 7,000 euros offered by the company to drop a court case – with no certainty of winning the court battle – was, at least for me, a considerable financial stretch. It was a hard decision given my situation, but I was able to make that decision. I wasn’t able to graduate until I had paid my university fees, and I went through some very difficult months, juggling multiple formal and informal jobs from Monday to Sunday. Even so, I do not consider my decision to be more worthy than those who chose another path, it is a reflection of the different starting points in which social inequality places us.

All this gradual mutation of working conditions was key in drawing the lines of a new framework of labour relations that the platforms were set to impose as a fait accompli, bypassing existing regulation. However, the main innovation that served as a springboard for this transformation was not made up of contracts, papers or rules, but of seemingly blind mechanisms, with no free will, programmed to organise work on the basis of impenetrable instructions.