I

This book that you are holding in your hands is the history and present of a struggle that begins the day that your life explodes into a thousand pieces. Your children’s life has already done so, but yours implodes in the moment that you become aware of it. The day that your child reveals to you that their father touches them down there or the doctors explain the cause of that constant vaginitis: the signs that you had not previously been able to interpret connect and there is no going back.

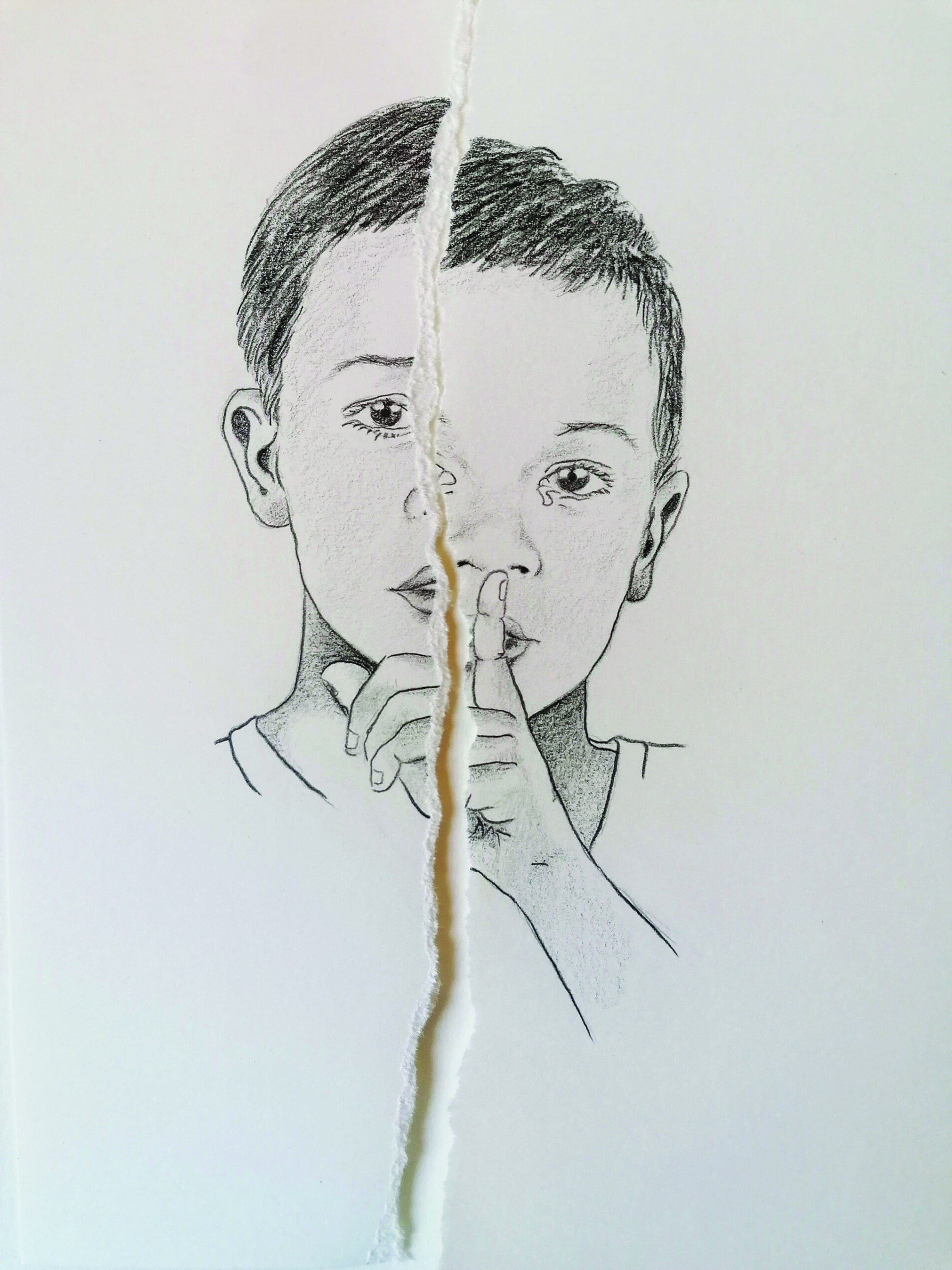

Our mothers kept their mouths shut, our mothers’ mothers did too. We do not. At first, it is is almost automatic. Now that we have learned to say no to violence against our bodies, how could we consent to it against our daughters (our sons, our non-binary children)? We consult professionals, we do research, we investigate, and, when we see that there is a high level of credibility to what our children are telling us, we file a report. And then we enter an even greater hell. We soon learn that we are not only confronting our child’s abuser. Their father is not only their father. He is the Father, the incarnation of the pater familias, that figure that sustains a whole social order that the judicial system does everything to protect. It would appear that the social and gender mandate to protect children ends where the pater familias appears, but what is certain is that our conviction of our duty of protection does not exclusively correspond to external mandates nor is it exhausted in imposed limits. Thus, when institutional violence befalls us, we have to choose. And we choose to keep going. We choose to not be silent. We become protective mothers.

The fear and pain that we face are so great that we understand those who have to stop and return to silence. We have chosen to continue until the end. Until our children can return home and be safe from their abusers. Until the whole truth is recognized, until we achieve justice, and all the pain that has been caused is repaired.

The first times that we came into contact with the protective mothers, we could not contain our tears as we listened to their stories, torn between bewilderment and horror. It was impossible not to feel moved. At first, our tears were contained. As our bonds deepened, tears started flowing freely to accompany us and hold us there where words don’t reach. Humor also emerged, that ironic escape that alleviates tension, that allows us to imagine other futures.

As we read the medical reports, psycho-social evaluations, and sentences, it became necessary to write each other constantly, call one another, even in the middle of the night, to share our disbelief with those close to us, because it was becoming unbearable to keep it to ourselves: How is it possible that they are not listening to what that child is saying? How can they question such a compelling medical report? How can a social worker be so judgmental against a mother who files a report on behalf of her child? Why can they not see the fear in that girl’s body? How is it possible that, all of a sudden, it is the mother who has to prove her innocence and not the accused father? How can a trial be overturned in such a way?

Here, between the pain, the rage, the bewilderment, but also starting from determination, admiration, and feminist embraces, we embark upon this book together.

II

The following pages were written by us protective mothers in alliance with other people touched by this struggle. We aspire to put words to that immense taboo of incense and paternal sexual violence. The silencing that surrounds this taboo is so strong that official data is not even collected on the issue. The European Council calculates that sexual violence affects one out of every five children before the age of eighteen. The picture is completed when we bring together that statistic with another from the macro-survey on violence against women carried out in Spain in 2019: in 40 percent of cases of sexual violence suffered before the age of fifteen, the aggressor belongs to the family environment: the father, the mother’s male partner, a brother or another male in the family.

The surprise generated by these statistics speaks to the extent to which paternal sexual violence in early childhood is an unthinkable and unnameable phenomenon in our societies. Starting from the impenetrability of that place, an intricate judicial web is spun in which we, mothers denouncing sexual violence by our children’s father, find ourselves: nobody believes our daughters and we ourselves are accused of being liars. It seems easier to imagine malleable children and an instrumentalizing and vengeful mother than a father who would rape his own progeny. This is what parental alienation syndrome is all about: an interpretive framework that makes us mothers who file reports appear as obsessive and perverse women who manipulate our children into lying in order to take revenge on their father. It is a framework that absolves that father of any suspicion, discouraging mothers and professionals from filing reports and moving forward with legal proceedings, that takes our children from us, that leaves them completely unprotected, and that lands us in jail or facing fines that are impossible to pay.

With this book, we seek to tear down the opacity of the judicial system and child “protection” mechanisms, unravel their mechanics and expose the falsity of parental alienation syndrome to reveal the type of institutional violence that we are subjected to and the generalized lack of protection for children who are sexually abused by their fathers. In doing so, we also seek to denounce the subtle mechanisms of a patriarchal backlash that finds a good ally in (certain) courts. This backlash takes us as scapegoats, but it goes beyond our individual stories. In a widespread offensive against feminism’s victories, it weaves together gender mandates, patriarchal myths, and the incest taboo to call us—mothers and our children—to order, protecting, above all, the sacred character of the pater familias and the institution of the family over which he presides.

II

Having set ourselves this task, we embarked on a collaborative research and writing process, in which the writing skills of some have been woven together with the legal knowledge of others, in which first person experiences have been woven together with data and bibliographic searches, in which the rage of many has set fire to the pages: rage at the sexual violence that has been experienced, rage at the lack of protection for children, rage at the omnipotence of the pater familias.

The book’s structure, the concepts that articulate it, and the first brushstrokes of its content were illuminated in a workshop with protective mothers. Later, the text acquired depth as it was written by several hands, using first-person testimonies, shared reflections in collective work sessions, psycho-juridical reports and sentences, as well as prior studies and essays about sexual violence, parental alienation syndrome, and institutional violence. After several rounds of revisions by survivors, protective mothers, journalists, doctors, jurists, and feminist activists it reached the shape that it takes today.

Deciding what parts of this struggle to narrate and how to do so has not been easy. The medical, psycho-social, and expert reports, the sentences, archives, resources and allegations from a single case cement a thousand page monster that contains all the violence that we, us and our children, have suffered. Sharing them publicly, in detail, would have made our complaints irrevocable, but it would have also left us even more exposed than we already are. We live under a constant threat of criminalization. Our enemy is strong and has many tentacles that go beyond the judicial system (police webs, child abuse networks, influential media, university departments, far right political parties, etc.). Therefore, we have chosen to remain anonymous and take shelter behind the names of allies. This book’s collective authorship represents precisely that: the impossibility of putting our names to our stories for fear of what could happen to us afterwards. It also speaks to the fear that our names will be not be enough to fight the disbelief awaken by our struggle, disbelief fueled by the media and judicial lynching that we have suffered. Ultimately it embodies the support of our allies, who sign this book as a way of putting their bodies on the line in solidarity.

Protecting our daughters pushes us even further, if possible, to take extreme precautions. Their right to privacy, to not be recognized in their everyday environments, the possible reprisals they might suffer from their fathers were this book to fall into their hands, the details that, from their current situation of helplessness, they might accept and those that are better saved for later, when they can get out…, all of this has led us to take refuge in literary language when sharing our struggle. We have fled from legal technicalities, that dense jargon with which we have been forced to familiarize ourselves, but that constitutes, in its distancing effect and opacity, another form of institutional violence. On occasion, we have also relied on archetypes not only as a literary resource that allows us to remain anonymous, but also because a similar pattern is applied to all the cases that, at the same time as it tears us apart, also unifies our struggle. The UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women identified “a ‘structural pattern’ in the Spanish justice system that leaves women and children unprotected and discriminates against women,” which has been confirmed by a study by the Complutense University of Madrid, the University of Barcelona, and the Human Rights Institute of the University of Valencia.

When we are contacted by other protective mothers who are still in those first moments after filing a report and we see how parental alienation syndrome is invoked in their proceedings, we would like to be able to tell them not to worry, that the nonsense will stop sooner rather than later. But we cannot. In fact, we can anticipate, without much fear of being mistaken, the web that will begin being woven around them. Step by step, thread by thread. And the fact is, our cases are not isolated arbitrary events or injustices caused by chance or the malice of just one or two people. They correspond to a logic, that of the patriarchal justice system that uses parental alienation syndrome like Cerberus, that three-headed monster that guards the gates of the underworld, so that family secrets cannot get out and change cannot get in.

There is a pattern that is applied to us, but this does not necessarily lead to linearity and coherence in terms of what happens to us. This spider’s web, in its pattern, envelops us in a tangle of confusion and incomprehension. If, through reading these pages, you are left feeling confused and like you don’t understand, it is not because of the mixing of voices and stories, that is exactly what each one of us experiences as the judicial threads are knotted around our bodies, until we find ourselves like insects flinging ourselves helplessly in the center of the spiderweb. This will all start making sense, little by little, over the course of this book. Each reference to proceedings, reports, and sentences corresponds to specific cases and real acts, except for when it has been necessary to resort to metaphorical language to protect the identifies of those who risk everything in this. With bits and pieces from here and there, we have tried to compose a narrative that conveys our experiences in all of their suffocating reality.

We have accompanied the narrative of what we have experienced as protective mothers with another story that is more linear: the chronicle and counter-chronicle of the process of criminalization experienced by the Infancia Libre association, the first organization to visibilize our struggle, and which paid a high price for doing so. The headlines and their counterparts, which were never told or can only be read in the footnotes, the details that change everything, help us understand how a handful of ordinary woman became the primary target of a ferocious media, legal, and political attack. To complete the puzzle, we have added accounts from the other side, that of children exposed to paternal sexual violence and different forms of the lack of protection. We want to thank their authors for their courage in sharing their experiences in order to protect others.

Some texts are supported by what we call “concept sheets.” These consist of detailed descriptions of some of the key terms of this struggles, as well as narratives and testimonies that help visualize how something that seems very abstract is translated, in a very concrete way, into the lives of women and children. These texts can be read in order or jumping around, like a glossary. They aim to situate, with descriptive and analytical materials, people outside of this suffocating spiderweb that traps protective mothers when we try to protect our children from paternal sexual violence.

IV

The struggle of protective mothers emerges from earth-shaking movements, in the collision between the same old patriarchy and the recent achievements of the feminist movement. More than a decade of feminist tide has helped children achieve sovereignty over their own bodies and identities. It has also encouraged mothers to listen to their children in a new way, to value and believe their experiences and words, even if these contravene family harmony.

Keeping the father happy is no longer the priority. The pater familias reacts to that rebellion—self-determination—of those who, not so long ago, were under his control: he deploys all the resources at his disposal to reaffirm his power.

Listening to this struggle, that of the protective mothers and children who raise their voice, illuminates a set of urgent vectors of politicization for the feminist movement. First, it allows for visualizing the patriarchal root of our justice system. As Miren Ortubay reminds us, the judicial system has never been a good ally to women. In our country, it played a key role in disciplining women and their sexuality during the whole Franco dictatorship. Among other things, it granted husbands the prerogative to apply a “corrective” to their wife and children when they did not obey them and, up until 1971, it exempted them from punishment if, when beating their wife caught in adultery, her injuries were minor. “My husband beats me the normal amount,” was a phrase endorsed in criminal court. Some of those judges continue exercising as such and have trained the following generations.

When a mother reports paternal sexual violence today, she is breaking the cannon of conjugal submission and maternal self-sacrifice. She is exposing, to everyone, the dirty laundry that, according to the patriarchal logic, should be washed at home. She is shattering that household harmony that, according to that logic, she should be protecting. Under the prism of the pater familias, this immediately makes her suspicious: of lying, of wanting revenge, of being manipulative, and, above all, of being a bad woman. Unfortunately, the stories of protective mothers show us that, despite the supposed impartiality of the courts, this perspective is in operation in not just a few cases. In the blink of an eye, the woman filing the report goes from being suspicious to being accused. When she sits on the witness stand, more than often, she is judged more harshly than anyone.

The struggle of protective mothers also reveals the adultcentrism that permeates the judicial system, which is incapable of offering adequate frameworks for seeing and listening to children. The lack of specialized institutional devices that specifically recognize childhood in its different developmental phases, coupled with the taboo of incest and the stereotype that presents children as a blank slate open to manipulation, leads to impunity for paternal sexual violence and prevents providing true protection for children and young people. No matter how much “the child’s best interest” is emphasized, their will, experiences, and voice do not count.

Lastly, the struggle of protective mothers brings to the fore a subtle and invisible violence: that which appears in an accusatory psycho-social report, which is prolonged in the school’s inaction, which is materialized in the judicial decision to remove children from the mother with whom they have lived with since birth.

The encounter with institutions that people initially approach in search of help multiplies the trauma: it forces you to relive what happened over and over again, revictimizing and shifting the blame onto those who should be receiving support. Judges, social workers, lawyers, forensic experts, prosecutors, etc. immersed in the constitutively patriarchal logics of the state, ignore their duty, as public workers, to protect and, instead, justify the violences that unfold. The banality of evil defined by Arendt sneaks into their offices, diluting their responsibilities and trivializing actions that include levels of violence that could be classified as torture. There is an ever more urgent need to identify this institutional violence, given the invisibility that defines it and the impunity that protects it

It is a violence that always leaves you defenseless, because it is not named, it is not even insinuated, but it pierces your soul. I feel like the justice system has its hands around my throat all the time. Hidden and exercised in a normalized way, it tolerates and legitimates all types of violence. Every time I receive a new notification or hold a report in my hands, I collapse emotionally upon reading it, my hands stiffen and I can’t move them for twenty-four hours. I cannot face my papers. They have taken the most beautiful thing in my life from me, the chance of caressing her, looking at her, protecting her, like my mother did with me.

The criminalization that protective mothers face is similar to the witch burnings of yesteryear. The patriarchal justice system—and society—wants to burn them at the stake for breaking the submissive and self-sacrificing role written for them, for daring to name and bring to light paternal sexual life, questioning the paternal right over the bodies of their offspring. These protective mothers have not come all this way to stay silent now. Their strength is ours. With us, with you, we will be a tremor that will shatter everything.

Notes

1 This booklet would not have been possible with the wisdom and generosity of the many people who collaborated in different moments of the process. We want to specially mention Mateo Álvaro, Isabel Cadenas, Lidia Larrarte, Miren Ortubay, Patricia Reguero, Ana Varela, Justa Montero and Marta Nebot. There are other names that we cannot mention due to the criminalization suffered by protective mothers and those who support them, but those women know who they are and we want to also express our gratitude to them.

2 European Council, “One in Five Campaign,” https://www.congress-1in5.eu/ See also, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions (2020): “EU strategy for a more effective fight against child sexual abuse” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0607

3 Macro-Survey on Violence against Women 2019, Subdirección General de Sensibilización, Prevención y Estudios de la Violencia de Género (Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género), https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/violenciaEnCifras/macroencuesta2015/pdf/Macroencuesta_2019_estudio_investigacion.pdf

4 Marisa Kohan (December 12, 2021): “La ONU ve un ‘patrón estructural’ en la Justicia española que desprotege a los niños y discrimina a las mujeres,” Público https://www.publico.es/sociedad/onu-ve-patron-estructural-justicia-espanola-desprotege-ninos-discrimina-mujeres.html

5 Débora Ávila, Adela Franzé, Patricia González Prado, María del Carmen Peñaranda and Marta Pérez (2022): Violencia institucional contra las madres y la infancia. Aplicación del falso síndrome de alienación parental en España, Ministerio de Igualdad https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/violenciaEnCifras/estudios/investigaciones/2022/estudios/violencia_alineacion_parental.htm

6 In Greek mythology, Cerberus was the dog of the god Hades, charged with ensuring that the dead did not leave his realm and that the living could not enter. In most ancient sources, he is described as having three heads, although Hesiod attributes him with fifty heads and a serpent instead of a tail.

7 Miren Ortubay (April 4, 2014): “Mujeres y castigo penal,” talk in the Mujeres encarceladas: castigo, feminidad y domesticación Series, https://ehutb.ehu.es/video/58c66d40f82b2b836e8b4574

8 See Article 428, Chapter V, of the Francoist Penal Code of 1944

9 Marta Cabezas and Ana Martínez (2023): Cuando el Estado es violento. Narrativas de violencia contra las mujeres y las disidencias sexuales, Manresa: Bellaterra.

10 Rita Segato (2018): Contra-pedagogías de la crueldad, Buenos Aires: Prometeo Libros.

11 Tania Sordo Ruz: “El uso del falso SAP como forma de violencia institucional”, in M. Cabezas and A. Martínez: Cuando el Estado es violento, cit., pp. 99-114.

12 Marisa Kohan (June 8, 2022): “Reem Alsalem, relatora de la ONU: ‘La violencia institucional que sufren las mujeres puede llegar a niveles de tortura’”, Público, https://www.publico.es/mujer/reem-alsalem-relatora-onu-violencia-institucional-sufren-mujeres-llegar-niveles-tortura.html

13 Fragments from voices of protective mothers who suffer institutional violence. Some of which are extracted from the report: Débora Ávila et al.: Violencia institucional contra las madres y la infancia, cit.